A Movie House on the West Side

There was a small film theater on the West Side where they showed German and Austrian films. The name of the theater is the only thing I forgot. It was frequented by elderly emigrés. The décor fit the audience. The walls ere embellished by candelabras. The atmosphere was compatible the films, which were mostly Thirties fare – films that had been made when old Europe was still old Europe.

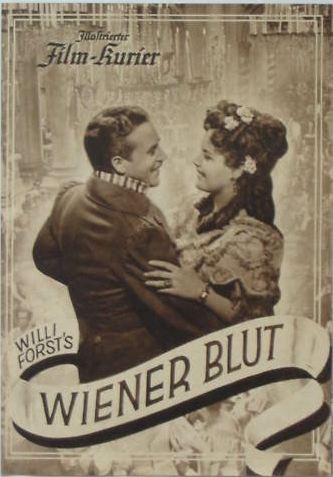

I remember a double feature I saw in the Fifties. Ditte menneskebarn (Denmark, 1946) and Wiener Blut (Austria then “Ostmark,” 1942).

Beautiful Ditte went through much of her film topless, and that of course was visually pleasurable. Such occurrences were limited to foreign films at the time.

Wiener Blut, an “operettic” film, was directed by Willi Forst in 1942. Forst directed and acted in musical films before the Third Reich period and during that period. He continued going his musical way after Nazi Germany had annexed Austria, but he never engaged in propaganda. When Veit Harlan, the director of Jud Süss, called him and offered him the leading role, Forst shouted into the receiver: “Are you out of your mind?!”

As the titles of Wiener Blut came on to waltz music in that old New York movie house, you could have cut through the nostalgia with a knife. The audience was transported to days gone by – days before ’33 in Germany and ’before ‘38 in Austria. Elderly eyes moistened. Yes, those were the good old days in the old country. Those were the days before Berlin blood and Viennese blood was shed.

The shedding of blood may have been staunched, but days prior to that shedding were gone forever, but now one viewing a film which showed the spirit of days gone by, the spirit of how things were – or how they were envisioned.

Willi Forst depicted those days in Austria. It was his specialty. Perhaps he sprinkled too much confectionary sugar on his cinematographic concoctions, but there was some truth to it. It may not have been quite that way, but all in all you couldn’t say it wasn’t that way at all.

The film that was being viewed was made in 1942. That was not the way things were at all at the time. It was a time when murder became methodical and gained momentum. It would accelerate until it reached its peak. The deportations of those who had remained in Europe had begun would soon be in I full force.

Yes, but on the screen of that movie house you could see a film with light-hearted music and song.

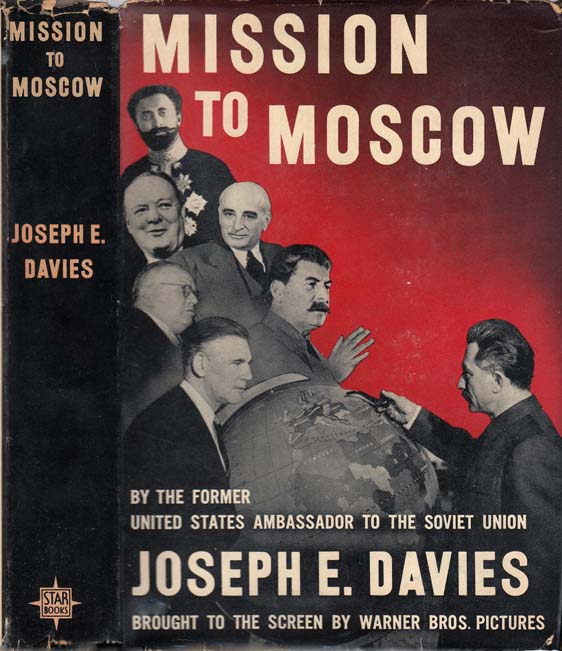

Mission in Propaganda

Mission to Moscow was Michael Curtiz’ follow-up to Casablanca in 1943, with another script by Howard Koch. This non-masterpiece was made at the request of F. D. R. Curtiz was renowned as a cynic, and maybe that’s his excuse. What the hell, if the president says do it, who was Curtiz to quibble?

Our ally of the time Josef Stalin is not only made palatable, he is presented as a man to admire. The show trials of Stalin’s fellow revolutionaries in the film are legitimate legal procedures, in which all confess to being Trotskyite traitors in the pay of Nazi Germany. And these blackguards get their just deserts, which conveniently occurs off celluloid. There is no mention that Stalin had Trotsky polished off in Mexico, two years prior to the release of the flm.

The Allies needed the manpower of the Soviet Union to defeat Nazi Germany. Was Mission made to butter the dictator up? Did Stalin need such cajoling in order to fight on? And what was the purpose of presenting such fabrications to film theater audiences of the time?

The Russians bore the brunt of the fighting, and their losses were over twenty million, which didn’t faze Stalin in the least. After the war, he added to the casualties by transferring Russian prisoners of war and slave laborers to the gulags or killing them outright after repatriation. Only a traitor would let himself be captured or work as a slave for the enemy. But that lay in the future when the film was made.

Here we have a rose-colored evaluation of the invasion of Poland by the otherwise great Winston Churchill on October 1, 1939: “We could have wished that the Russian armies should be standing on the present line as the friends of Poland instead of invaders. But that Russian should stand on this line was clearly necessary for the safety of Russia against the Nazi menace. At any rate, the line is there, and an eastern front has been created that Germany does not dare assail. When Herr von Ribbentrop was summoned to Moscow last week, it was to learn the fact and to accept the fact that the Nazi designs upon Baltic States and upon the Ukraine must come to a dead stop.”

Oh, yes indeed they came to a dead stop in June of 1941. Could Stalin’s decimation of the general staff have had to do anything with that?

Here’s Churchill again on May 24, 1944: “Profound changes have taken place in Soviet Russia. The Trotskyite form of Communism has been completely wiped out.”

“Hallelujah!” is my comment.

This certainly is one of Churchill’s least admirable quotes. Trotsky was ruthless, as he proved by brutally quelling the sailors’ uprising in Kronstadt, but he was a military man and a man not only interested in power for its own sake. If he had prevailed over Stalin, the Soviet army would have (at least) stood its ground against the Wehrmacht.

Yes, Trotskyism was wiped out, as was Trotsky. Stalin had him in mind in August of 1940 when his hit man polished him off in Mexico. What he did not have in mind was preparing for an invasion by Nazi Germany.

The fact of the assassination is conveniently omitted from the Mission film, as well as from Churchill’s evaluation.

I know, I’m writing in hindsight: Stalin’s participation in the war certainly was essential, but was it necessary to kiss a mass murderer’s ass?

to be continued . . .

– Herbert Kuhner

Users Today : 39

Users Today : 39 Users Yesterday : 138

Users Yesterday : 138 This Month : 3520

This Month : 3520 This Year : 9579

This Year : 9579 Total Users : 191384

Total Users : 191384 Views Today : 133

Views Today : 133 Total views : 1894424

Total views : 1894424 Who's Online : 3

Who's Online : 3