Homage to the Thalia

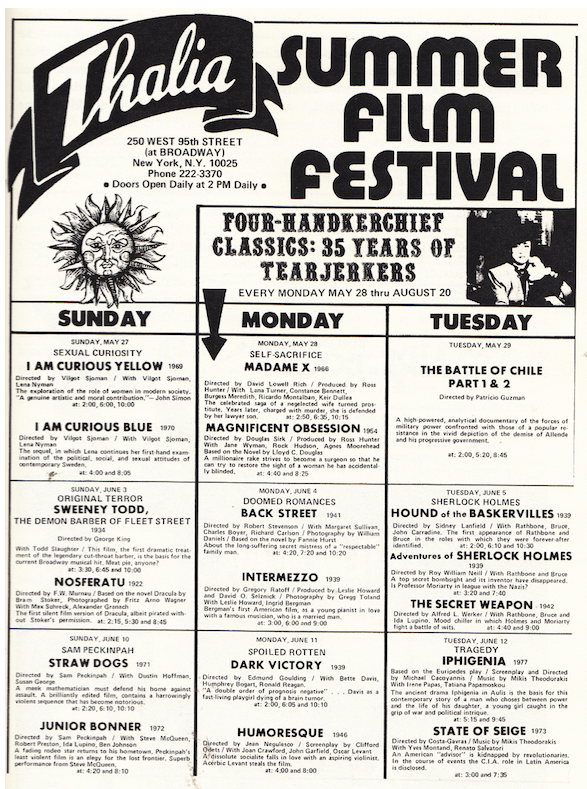

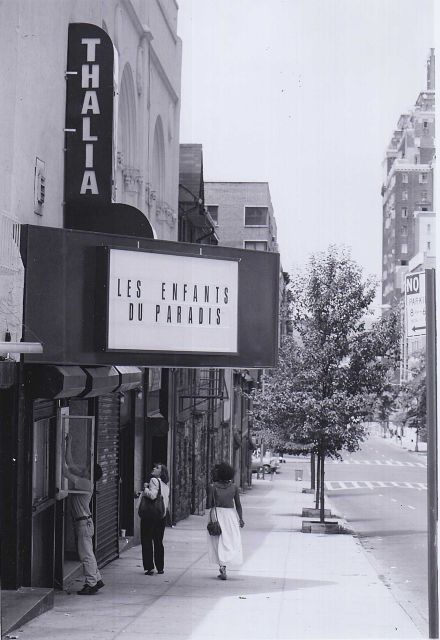

I remember the old Thalia well. It was located off Broadway at 95th Street. The daily fare was two foreign double-feature films with subtitles which were shown for the duration of a day. There was an elaborate folded program on which the films were invariably described as “masterpieces.” Most of the films were French. They were directed by such masters as René Clair, Julian Duvivier, Marcel Carné and Jean Cocteau. The names alone are music.

You went to see Hollywood films in theaters that resembled Moroccan palaces. Some of the films were black-and-white, but many were in Technicolor. I saw a lot of good ones at those venues, but the Thalia is where I got my education. It was the antithesis of being luxurious. Rundown and ramshackle is the best description. The films were the “Vielle Vague.” The Nouvelle Vague had not yet struck the cinematic shore.

I frequented the Thalia in the mid-Fifties while I attended Columbia. I spent hours and hours sitting on its hard, uncomfortable seats, watching black-and-white French films of the Thirties and Forties. Now and then, the film would break and you had to wait for it to be spliced before you could continue watching it.

Yes there was irritation and discomfort, but film is the thing.

What can I say? Where else could I have seen those wonderful French films? I don’t know what my life would have been like if I could not look back on the Thalia.

Attending the Thalia was like drinking vin ordinaire to a crisp baguette – or in other words, a fare of nectar and ambrosia.

Remember the Days!

Who was Lincoln Theodore Monroe Andrew Perry? He was Stepin Fetchit? Who dat? Here’s Stepin to provide he answer: “I was the Sammy Davis of the Stone Age.” Stepin was the “sacred nigger” of the Thirties and Forties Bs. He’d turn up on his tiptoes with eyes bugging when there was a threat of gangsters or ghosts. He was good for a laugh or two. Stepin was a nice fellow who wasn’t too smart and he was just plain scared when he thought that danger loomed.

Stepin Fetchit

That’s how we saw blacks in those days. The women were mammies and the men were “Stepin.” (Actually his Jewish counterpart was Jerry Lewis, who was the stereotypical schlemiel. But that cliché lasted longer.)

High Sierra, directed by Raoul Walsh in 1941, stars Bogey as gangster on the lam and Ida Lupino as his loyal girlfriend. Bogey’s star was rising and he’d go on to Casablanca. Ida’s star was falling and she’d go on to starring and directing Bs. Walsh was a good and successful director, but he stooped in Sierra to using Stepin for a few cheap laughs.

The “Stepin” image was so ingrained that even one of Hollywood’s best directors apparently couldn’t free himself from it.

Thank God those days are over!

From Stromboli to The Visit

Ingrid Bergman left Hollywood to make Stromboli for Roberto Rosselini in 1949. Her intention was to leave Tinsel-Town glamour behind her to in order make neo-realistic European films. And Roberto’s manly appeal may have influenced her decision. Roberto had made Roma, Open City and Paisa, which are indeed stunning. Some film buffs love the films he made with Bergman. I think Stromboli was so-so, but that all the others were duds.

Twenty-five years later she starred in a film version of Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s The Visit directed by stickler Bernhard Wicki, which was a European production. Wicki had died a thousand deaths when he filmed Morituri with Marlon Brando. Brando had moved Heaven and Earth to get Wicki on the set, but once he had him, he made Wicki regret that he had ever been born. And the result of Wicki’s tribulations was nothing to be proud of. Ditto for Ingrid.

In Dürrenmatt’s play, an unattractive, crippled old lady returns to her hometown as a wealthy, powerful revenge-seeker in order to bring about the lynching of the man who seduced and ruined her. However, in the film “the old lady” turns out to be younger, attractive and with limbs intact. Instead of having her quondam lover, the present mayor, done in, she relents and shows mercy.

Thus Bergman rewrote and “glamorized” one of the most significant and successful contemporary plays, riding roughshod over author and director. And Hollywood celebrated a triumph over realism, neo-realism, surrealism and what-have-you, albeit in Europe. And thus Bergman propelled herself right smack back to the spirit she had left behind in Tinsel Town.

to be continued . . .

– Herbert Kuhner

Users Today : 35

Users Today : 35 Users Yesterday : 138

Users Yesterday : 138 This Month : 3516

This Month : 3516 This Year : 9575

This Year : 9575 Total Users : 191380

Total Users : 191380 Views Today : 112

Views Today : 112 Total views : 1894403

Total views : 1894403 Who's Online : 5

Who's Online : 5