Goodbye Leni!

Leni Riefenstahl has left us at the ripe old age of one-hundred-and-one, and the old debate concerning form and content has come to the fore again.

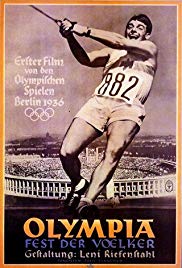

Doubtlessly Riefenstahl was a master cinematographer and an innovator. She approached Hitler with admiration in the twenties, and after he took power, he became her patron. He presented her with the opportunity of directing a film glorifying him and the Nazi party and a second film that should have glorified the Master Race. She accepted both commissions and delivered two films that are masterfully constructed. Triumph of the Will and Olympia, which were made in 1934 and 1936 respectively.

Let’s have some recent comments by Riefenstahl! Here are her own words concerning her work: “Everything in Triumph of the Will is true. The film is a purely historical film, a documentary, not a propaganda film. My films do not contain one single anti-Semitic word. They are Stubenrein (which translates as ‘housebroken’).” Does that mean that there is no brown element in them?

Young Leni didn’t simply have a cameraman stand there with a camera. Cameramen were placed everywhere to film the proceedings from all angles, and when the film was cut it wasn’t just spliced together. The intent of the film was to glorify Hitler and the Nazi Party. And that it did with flying colors.

Hitler und Riefenstahl

But, in her defense, Riefenstahl did hit a note of truth. The film presents an accurate picture. Ruthless Nazi leaders are shown manipulating uniformed masses, which made up a military machine. And it is apparent that the machine was not going to be penned in. Indeed there is no mitigation. The film glorifies might, and the threat of what was to come can be easily discerned. The booted feet that marched in Nuremberg would march far beyond German borders.

Here’s a quote: “No anti-Semitic word has ever crossed my lips. I was never anti-Semitic. I did not join the party. So where then is my guilt?”

Apparently Riefenstahl has forgotten one scene in her masterpiece. In the second set of speeches, an anti-Semitic tract is explicitly provided by one of the lesser Nazi nabobs. I have not been able to get a cassette of the film so that I can jot down the speaker’s name and quote him. If anyone can lend one to me for that purpose, I would be more than grateful.

Leni did not join the party, but neither did most of those who were involved in the making of Jud Süss, one of the most infamous propaganda films. Goebbels forced artists tto work for him. He didn’t care whether they joined the party.

One the one hand Leni claimed that she was forced to make Triumph, and on the other, she said that she had offers from Hollywood, naming Douglas Fairbanks and Charlie Chaplin.

She said that she would also have made films for Stalin and Churchill, if they had forced her. Naming the latter is absurd, since only dictators forced artists. But I wager that if she’d filmed for Stalin, the cinematography might have been marvelous, but much less enthusiasm would have been conveyed. Some of the concepts might have been less appealing.

Leni went to the front as a correspondent when Nazi Germany invaded Poland in 1939, but was disgusted by the brutalities of the Wehrmacht and quickly returned to Germany. However, she sent a congratulatory telegram to Hitler after France had been conquered.

“Everyone thought the war was over, and I sent the telegram that spirit,” are her words.

Some feminists lay claim to Leni and close their eyes to what she and Triumph were all about.

American author Susan Sontag, who has also left us, was dazzled by Riefenstahl’s cinematography. Sontag admits that Triumph is Nazi propaganda but sees something else that should not be rejected. For Sontag, the complex mobility of spirit, grace, sensuality go beyond propaganda and even reportage, and reality ceases to be reality and Hitler ceases to be Hitler. The content plays a purely formal role.

You need form to say what you say, but what you say is the essence.

Leni claimed that she made no comment during the film. She didn’t need to. Her camera did it for her.

Leni was a “liberated” woman who aided unequivocally opposed to women’s rights, to put it mildly. As a filmmaker, she made a great contribution to spreading Hitler’s message of oppression.

When Leni made Triumph the war had not begun and mass genocide lay in the future, but Hitler’s intentions had been clearly stated, and she helped show them. Hitler and Nazism is what the film is all about. Deleting Hitler from it would be equivalent to taking Captain Ahab out of Moby Dick

A woman who served Adolf Hitler was the Devil’s handmaiden, and Leni Riefenstahl served the Devil and did his work well.

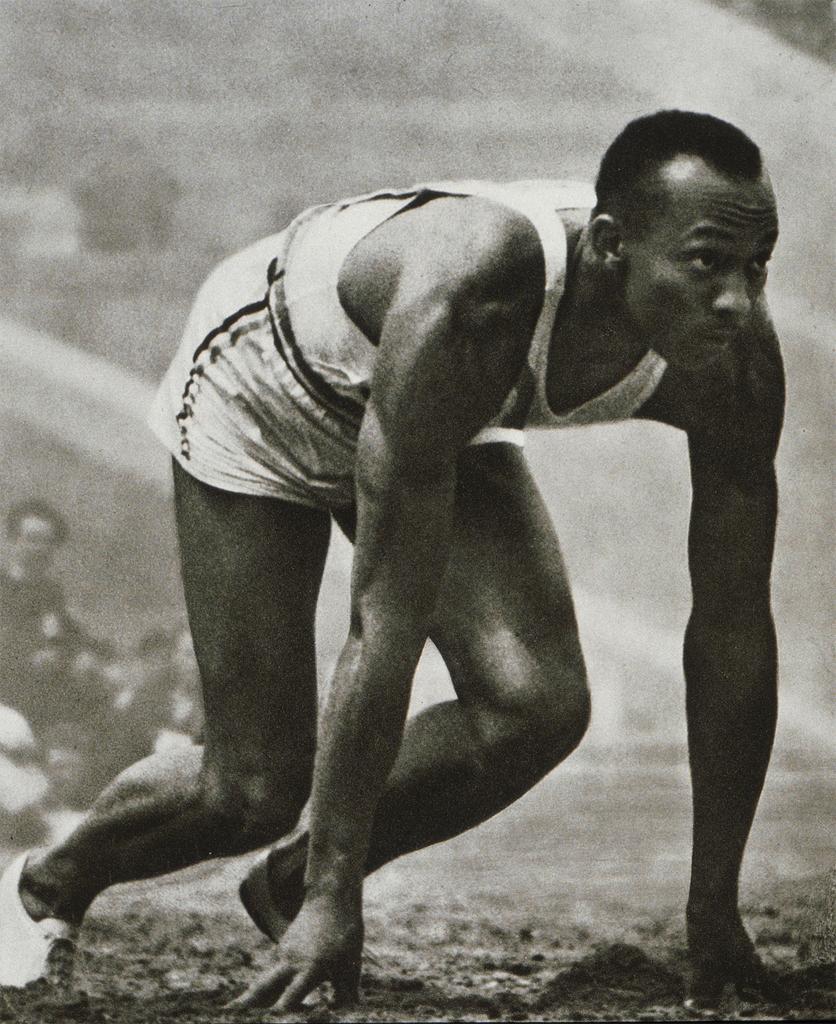

Olympia was to show the superiority of the master race in sports. Since the Olympic Games consist of contests, there could be no script for, and serendipity gummed up the works. Jesse Owens, a filmagenic black, won four gold medals in track events, and Owens’ black teammate Mitchell took gold for the pole vault. Even a master director can’t make winners look like losers, but Leni’s camera doted on them as lovingly as it had doted on the Nazi leaders in Triumph. She just couldn’t resist a good shot, even if it contradicted the thesis of the film. The film is splendid depiction of the Olympic events, but fails miserably in its propaganda purpose. Owens and Mitchell stole the show and they managed to botch up Olympia for Hitler and Goebbels. But in spite of the fact that two American blacks triumphed in Olympia, the threat manifested by Triumph became a reality that ravaged in Europe and Africa for six years.

Olympia was first briefly shown in Nazi Germany 1938, and in the following seven years of the Reich, Riefenstahl who was certainly not opposed to the cause, was not called upon by Goebbels to make another documentary.

The Star of Olympia

In 1935, the year the Nuremberg Laws were initiated, Leni Riefenstahl an ardent Nazi, directed Triumph of the Will at the location where the Laws were passed.

This epic starred a gesticulating little man in a brown uniform with a swishing cowlick, a toothbrush mustache and a coarse voice. That paunchy homunculus ranted and raved while a cast of thousands marched, saluted and shouted in unison.

Riefenstahl’ s second propaganda film was to feature representatives of the Master Race sweeping to victory at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, but something gummed up the works. Or rather someone undermined the thesis of the film. That someone in question was Jesse Owens, an American black. Jesse outran and jumped higher and farther than the baggy-pantsed, spindly-legged competition. The Tectonic representatives were left behind panting and gasping as an unbeatable black god ran and sprang his way to four gold medals. Jesse won with ease and his pants did not hang.

Those four gold medals were four insults to Nazi Germany and had torn four jagged holes in the Nuremberg Laws. In spite of the infamous laws, Mein Kampf and Goebbels’ “scholarly” tracts, the black man’s victory was fact and history. The cameras weren’t blind and film didn’t lie. Celluloid can be doctored up, but there are limitations for every camera. Riefenstahl may have been an ardent Nazi, but she was also a cinematographer and a woman. The static white nudes of the prologue were surpassed by the mobile black, who ran like a racehorse and sprang like a gazelle. Riefenstahl, in spite of herself, was more fascinated by that reality than the lie she had been hired to film.

The star of Triumph had pasty white skin and a five-o’clock shadow. The star of Olympia was a

beaming black god.

Jesse Owens

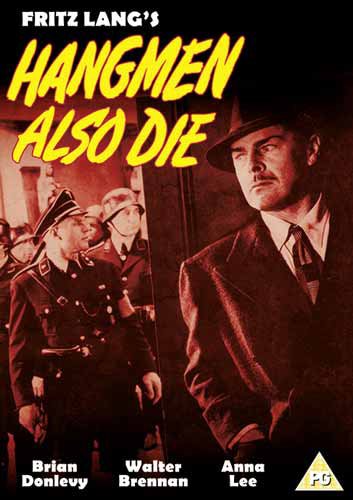

Hangmen Also Die

Hangmen Also Die was made in 1943 by Fritz Lang and originally scripted by Bertolt Brecht. It would have been Brecht’s only Hollywood film credit, but the great film director scrapped the great writer’s script, leaving Brecht with a legendary half credit.

I don’t know what Lang threw out, but what he left in lacks five minutes of drama. Brian Donlevy, the star, was a fine Hollywood supporting actor of the time. His specialty was playing officers referred to as „the old man“ on the Pacific front (when John Wayne wasn’t available), as well as film-noir gangsters and black-garbed villains in westerns. Hangmen was his only starring role, but it was nothing he could take advantage of. He must have known he was miserably miscast; since his acting and body language show his embarrassment. As a resistance gunman, he tip-toes around a papièr maché Prague set like Lon Chaney, Jr. playing The Wolf Man. The assassination story is complete fiction although many of the facts must have been known at the time. At any rate the great director produced a turkey, cooking the goose of all those involved.

Hangmen was one of the most marvelous titles in film history. Yes, Hangmen Also Die. Sometimes hangmen are killed like Heydrich, and sometimes they die of natural causes. The film Heydrich was shot by Donlevy, who was playing a good guy for a change.

The real life Reinhard Heydrich, „Protector“ of Bohemia and Moravia, was wounded by Czech partisans parachuted down by the British to do the job, and he passed on in the hospital. Some historians claim that since he was almost as popular among his fellow Nazi nabobs, as he was with his “Czech subjects,” orders were given that there was to be no recovery. And orders were given to wipe out the town of Lidice as a reprisal.

The day of the out-and-out villain like Heydrich is gone forever. There may still be a few around, but the fashion has changed. Today’s hangmen use ethics as a cosmetic, and they prefer to use a spiritual noose. Their aim is to have you to act as your own hit man, or at least to bring you closer to death. And they can keep their hands clean in the process.

Villains are better manipulators than men of integrity, so they can more easily attain posts, which entail acting beneficially and benevolently. The present-day variety is fawning, obsequious and patronizing. He invariably does charity work and is active in humanitarian causes. This puts him in a better position to do what he does best. It’s a tried and true method. Look at the Mafia! It builds hospitals, orphanages and old age homes. And it puts the first two to good use and helps to prevent the third from becoming a necessity.

Thus, we must concentrate on the positive aspects and give villains their due. And isn’t it better that some good is done rather than none?

Villains as well as heroes have to die, just as the man on the street must come to that end. In fact the impetus to write this came when I got the news that a prime spiritual assassin had passed on. There is something so pitiful about a man who has spent his life scheming and doing harm when he enters that final phase. When his time comes, he just doesn’t pass on like hangman á la Heydrich. He tries to keep up appearances before the Grim Reaper takes him, and he goes out singing Hearts and Flowers and other sad songs.

These melodies fill me with nostalgia for the out-and-out villain who was what he was and made no bones about it.

to be continued . . .

– Herbert Kuhner

Users Today : 238

Users Today : 238 Users Yesterday : 122

Users Yesterday : 122 This Month : 2675

This Month : 2675 This Year : 19608

This Year : 19608 Total Users : 177703

Total Users : 177703 Views Today : 342

Views Today : 342 Total views : 1868377

Total views : 1868377 Who's Online : 74

Who's Online : 74