The “Old Man”

You couldn’t call John Wayne versatile. But you couldn’t say that he didn’t do what he did well. He was not that young when he became a star. He mostly played cowpunchers who were over the hill or officers who were called “the old man“. The cowboy garb and the officer uniform fit him to a T. Well, good old John did ride horses in private life, but the prototype officer only fought in wars on the silver screen.

Here’s a quote: “All battles are fought by scared men who’d rather be someplace else.”

That “someplace” was the silver screen.

John Wayne

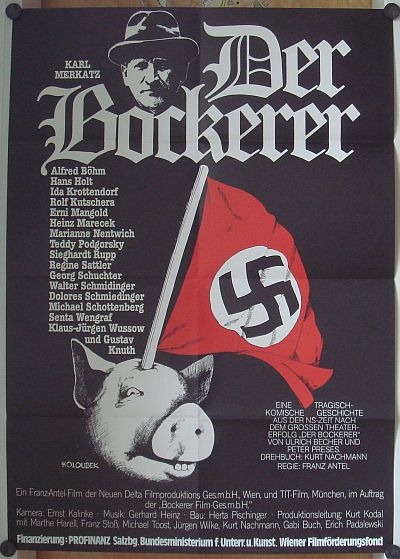

The Buck as a One-Act Play and Short Feature Film

There’s a man who shot off his mouth for seven long years in Austria. There are others who have done it for longer, but not under the circumstances. The guy I’m talking about did it between 1938 and 1945. At the time Austria was not Austria, but “Ostmark.” So that makes a difference. By doing that at the time, he was, of course, unsurpassed. His name was Karl Bockerer. Regretfully Karl was not a real person. He is the hero of the play Der Bockerer by Ulrich Becker and Peter Preses. Bockerer is their only success. It is one of the most popular Austrian plays, but the playwrights couldn’t follow up.

During the time Austria’s incorporation in the Third Reich, Karl says everything that should be said. And he doesn’t whisper, he shouts. Imagine that! And he’s there at the end of the play to welcome the Russian liberators before the curtain comes down. Karl is a butcher who speaks his mind to the Nazi butchers. But somehow, due to his charm they don’t butcher him.

The play belongs to the category of what’s called “boulevard theater” in the German-speaking world. Translating the word is easy since boulevard = boulevard. But there is no translation for the term. A boulevard play is entertaining with plenty of laughs with no serious aspirations

Anyway, the Austrian director Franz Antel filmed the play in 1981. That year the film received a prize at the Moscow Film Festival. It was followed up by three sequels. Becher and Preses couldn’t do the scripts since they are long dead.

Antel, at one time called Hans Weigel, an Austrian writer “a lousy Jew!” and added. “I was a Nazi and I’m proud of it!”[2]

Here’s a quote by Weigel “Austrians have a reputation for being anti-Semitic, but I’m relatively popular….I never made the acquaintance of an anti-Semite.”[3]

Apparently he forgot.

The play of course is the wish-fulfillment of those who kept their mouths shut and those who like to think there were anti-fascist loudmouths at the time.

In reality, anyone who bucked the system did not do it for long. The curtain would only have come down once. The denouement would have been the gallows or the guillotine. There would only have been one act in the play, and its duration would have been very short – from five minutes to a quarter of an hour, at the most.

White and Black Knights

The Wehrmacht made a semblance of chivalry when it began to conquer in the West, but later when victories ceased and frustration set in, that semblance was abruptly truncated.

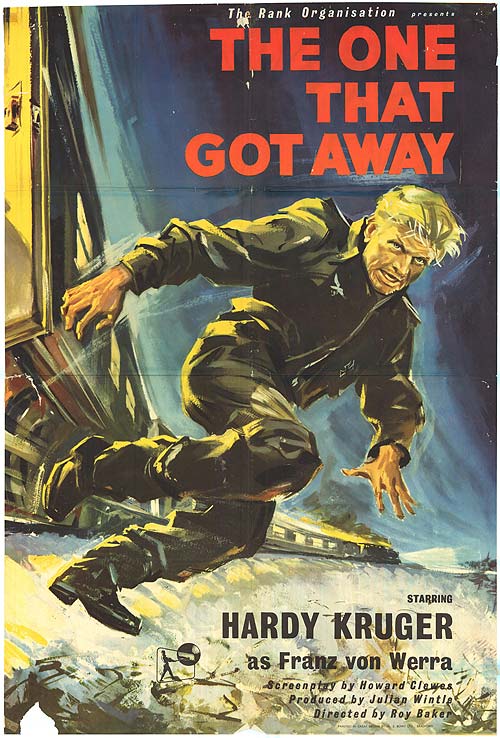

In the Fifties British and American films often depicted the war as a chivalrous encounter between valiant knights. The Colditz Story, Reach for the Sky, The One That Got Away, and The Desert Fox, to name a few, come under this category.

The White Knight, to be sure, were the British and Americans. The Black Knights were Germans. Even if they fought valiantly though as individuals, they formed a shield for the barbarism of the Third Reich. If these Knights had brought victory to the Nazi Germany, the “Dark Age” so aptly referred to by Winston Churchill, would have covered Europe and large part of Asia.

The first installations that were set up in conquered territories were those intimate little torture chambers and charnel houses. The mass charnel houses, which were equipped with the means for making aerial gravesites, would be constructed far off in the East. A million-and-a-half children would be among the unburied victims there. The One That Got Away is the true story of Luftwaffe-pilot Franz von Werra, who escaped from a prisoner of war camp in Canada, and makes his way be to Nazi Germany to fly again for Hitler. Von Werra’s resourcefulness is presented with admiration. His politics are not mentioned in the film at all.

After his escape in 1940 von Werra flew again to shoot down allied planes for a period of months, before being shot down himself in a fatal crash in 1941.

Hardy Krüger the star of Got Away, half a century later, questions about von Werra’s politics. When the film was made back in 1958, no one seemed to be interested in that aspect of the hero.

[2]Münchner Merkur, Die Presse, Juni 1956; Franz Krahberger „Der Kritiker Hans Weigel oder Käthe Dorsch ohrfeigt Hans Weigel“ Electronic Journal Literatur Primär ISSN 1026 –0293.

[3] Hans Weigel, Man kann nicht ruhig darüber Reden, Styria Verlag, 1986.

to be continued . . .

– Herbert Kuhner

Users Today : 32

Users Today : 32 Users Yesterday : 138

Users Yesterday : 138 This Month : 3513

This Month : 3513 This Year : 9572

This Year : 9572 Total Users : 191377

Total Users : 191377 Views Today : 92

Views Today : 92 Total views : 1894383

Total views : 1894383 Who's Online : 5

Who's Online : 5