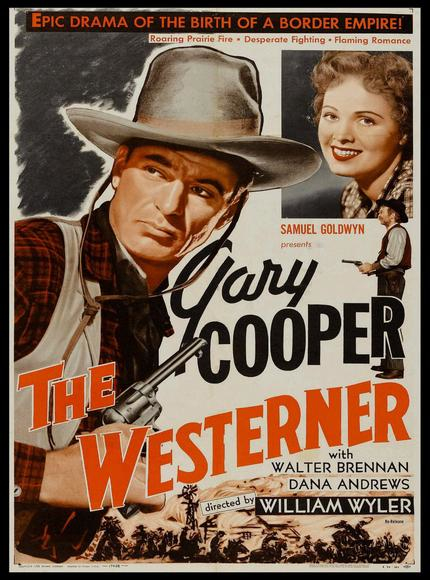

Henry V and The Westerner

The two love scenes in films that are indelible to me are between Laurence Olivier and Renée Asherson in Henry V and Gary Cooper and Doris Davenport in The Westerner. In Henry, Larry playing Harry proposes to Princess Kate after subjugating her country. He tells her that he is a man of action, not words and uses the most charming language imaginable to win her. He is, after all, the man who conquered France. His motivation for the invasion was having been slighted by her brother. The dauphin had sent Harry tennis balls to mock his playboy past. That’s the best reason for waging war that I ever heard of. And what revenge Harry took!

Renée was born to play the role. Larry’s first choice was Vivian Leigh. She was under contract to David O. Selznick at the time. He refused to let her do a guest appearance in Henry. Fortunately for the film and for Renée, Vivian, delicate beauty and a marvelous actress that she was, could never have brought the whimsical charm of Renée to the role. She’s a real sweetie-pie with a cherubic smile that has a hint of Gallic skepticism. She may have been playing the daughter of the daunted king of a subjugated country, but then how can she resist Larry as Harry the Conqueror, the handsomest and most elegant of men, whose lines were written by the Bard. His French is as bad as her English and there’s a bit of double-entendre-fun when he uses the word baiser, which is French for kiss but means more than a simple peck when used the wrong – or right way. The whole scene in which conqueror conquers conquered is so magical that you forget the unethical aspect. After all, Renée decides to hitch up with the man who defeated her father’s armies and displaced him as king.

In The Westerner, Gary, who’s playing a drifter, needs a lock of Doris’ hair for Walter Brennan, who’s playing Roy Bean, a sly but likable hanging judge. He’s told Roy that he knew Lillie Langtry and has a lock of her hair, both lies, and now he needs a lock for Roy, who’s just crazy about Lillie. He has to get it from Doris, who’s falling for him, as he is for her. So there’s a bit of dishonesty involved. The way he takes it from her is a simulacrum of the act. After he’s gone off with it in his pocket, she’s pensive, before she smiles joyously. Only Gary, tall and noble, and Doris with her innocent, homespun charm could have pulled it off. If John Wayne with his savvy and world-wise Claire Trevor had played the roles, they never could have made the situation convincing.

The next scene shows Gary opening small leather pouch, which contains a matchbox with the wrapped lock. As Gary slowly opens the box and then tenderly unwraps the lock from the protective tissue a gleeful Roy waits impatiently for it to emerge.

Roy’s a delightful fellow who’s also an ornery killer who continues to be what he is, and Gary has to go for him in the end. Lillie Langtry, who’s on a tour of the West, is appearing at the Opera House in Fort Davis and Roy buys out the house so he can enjoy the performance alone. But when the curtain goes up, Gary is onstage and there’s a shoot-out. After Gary mortally wounds Roy, he carries him to Lillie’s dressing room where the curmudgeon closes his eyes blissfully in her presence. Then Gary goes back to Doris who’s waiting for him. And that’s it. Fade out!

William Wyler

The director of the western is William Wyler, a German emigré, who brought a flavor to the film that couldn’t be more American. And there’s also a reverent Biblical quality to it that seems to pervade most classic westerns. There’s hoedown and the tragedy of destruction. In this film the cattleman-villains set the homesteader’s crops and houses alight and kill the heroin’s patriarch father.

Wyler, who directed Larry in Wuthering Heights, had been approached by Larry for Henry, but couldn’t tackle it due to other commitments. That meant Larry had to do it, which resulted in a masterpiece and started Larry on a career as a film director.

I first saw Henry at the age of 12 in 1947. My father took me to see it at the City Center in New York. It not only appealed to me as a story of heroism: the language captivated me. Up to that time, I’d been reading Dumas, Hugo, Scott and other authors of classics for young people. Henry was my introduction to Shakespeare, and started me off on world literature.

Olivier has ruined the play for me in a sense. For as long as I lived, I would never be able to enjoy another production. His Henry would always remain the production of productions for me.

Henry V was made as a propaganda film to increase the fighting spirit of the British armed forces. King Henry led a badly equipped army that was outnumbered by its foes. He defeats the enemy with a combination of courage and cunning. In World War II, the British defended their isle against a better-equipped and more powerful foe. They fought alone for a whole year before Hitler turned on his erstwhile friend Joe Stalin. But that is where the comparison ends. Harry fought the French on their soil to conquer their country. He had engaged in a war of expansion, using the pretext of personally being insulted, a paltry reason for conquest indeed. The insult consisted of a bunch of tennis balls sent by the French Dauphin to mock Henry’s playboy nature.

In order to show that his playboy days are a thing of the past, Harry sets out to conquer France. Does that sound as crazy as it is?

Shakespeare presents King Henry as a folksy hero and the French aristocrats as lofty and arrogant, but after all, it was their turf they were fighting on and for.

Contrary to the English and Germans of the war of the time, the English were the defenders, and the Germans, the would-be conquerors. In the play the English are the conquerors and the French, the defenders. But then, Henry as he is depicted was probably more humane to the commoners (the precursors of the common man) when he took over than his French counterparts.

In his monologues, Harry covers every aspect of war from the ethics of it to the horror of battle. But he opts for it, and he inspires his men to carry through to victory. He makes a “good” case for conquest and subjugation. But can even the great Bard really sell the idea of the conquest of a foreign country?

As a pre-teenager, although I was dazzled by the film, I had my doubts about that aspect. I could identify with the heroism, but not with the motivation for it. Yet it was that experience in the City Center, more than any other, that nurtured my love for language and my dedication to literature. Later, in order to develop my voice and get rid of a lisp, I tried to emulate

Larry’s voice and delivery. I used him as a model until I found my own style of reciting.

I waited in vain for Larry to assay another heroic role. After Henry came Hamlet, which did not quite fill the bill in that category. And then he went on to play villains and character roles with gusto and relish.

Yes, the great Bard wrote a marvelous dishonest play with the most utterly charming dishonest love scene. And I know that no could can ever play that scene as sweetly and beautifully as Larry and Renée.

Thanks to William Wyler’s refusal, Larry directed the film. And prior to that, thanks to William Wyler, Larry became the film actor he was. It was Wyler who purged him of his histrionic style for Wuthering Heights. Like many stage actors, Larry had previously had difficulty adapting to the film medium. And again thanks to Wyler for The Westerner which contains an equally charming dishonest love scene in which Gary and Doris match Larry and Renée in every way.

Charm isn’t always honest, but then what would art be without it? And for that matter, what would the world be without it?

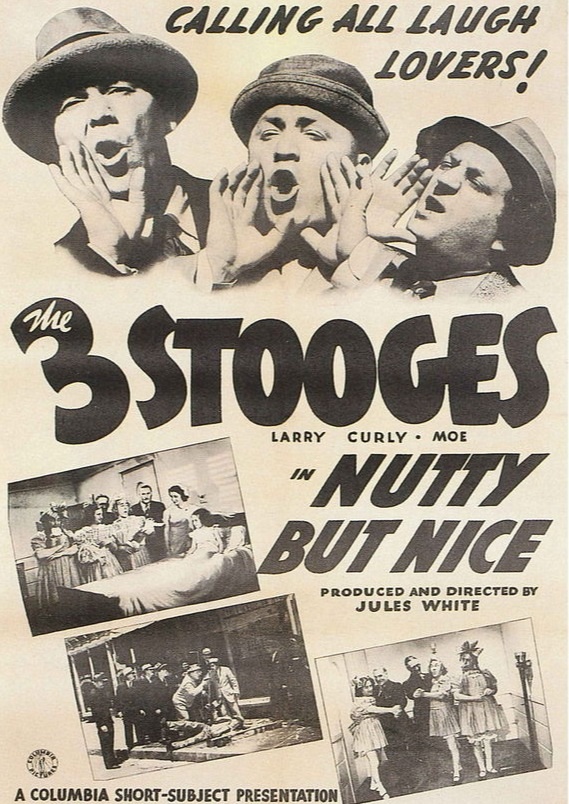

Homage to the Three Stooges

Manny, Moe and Jack are not the Three Stooges; they’re the Pep Boys. The Pep Boys used their first names after Moe saw a dress shop called Minnie, Maude and Mabel’s, way back in the Twenties. The Pep Boys didn’t have an act. They were the owners of the Pep chain stores for auto parts.

The Ritz brothers, Hal, Jimmy, and Harry did have an act. They took the name “Ritz” after seeing the name on the side of a laundry truck. There was, however, nothing ritzy about them. They were a sort of B-film ersatz for the Marx Brothers. But they never approached the popularity of the Marx Brothers, who were the intellectual elite of all threesomes.

The Ritz Brothers

The three Stooges: Moe, Larry and Curley, had absolutely no intellectual pretensions. Their films were pure slapstick, with Moe giving – and Curley’s bald pate – getting most of the blows. Bonk was the sound most-heard between lines.

Although the Stooges provided comic relief in such prestigious celluloid ventures as Dancing Lady, a Joan Crawford vehicle, their own films were not even the B-part of a double-feature bill. They mostly starred in short subjects, which were sandwiched between the A-film and the B-film.

The Stooges are my favorite threesome. I first saw a Stooge film in 1940 in New York at the age of five, and they never wore off. To me, they’re in the wacky category of Spike Jones, only minus the instruments.

My sophisticated friends are aghast when I tell them that the Marx Brothers put me to sleep, but the Stooges keep me awake. Their films are not weighed down by a silly plot, and there’s no sappy romance to slow things down.

I can’t help it, I’m a Stooges fan. And I’ll be one to the end.

Speaking of an end, the Grim Reaper broke up the act by removing Moe from the scene. And with Moe gone, who would deal out those blows? No, without Moe, it was just no go!

In 1975, the Ritz brothers were called upon to fill in for the Stooges in Blazing Stewardesses. But soon after the release of that cinematic masterpiece, the Reaper broke up the Ritz’s act too.

Bonk!

to be continued . . .

– Herbert Kuhner

Users Today : 78

Users Today : 78 Users Yesterday : 196

Users Yesterday : 196 This Month : 3384

This Month : 3384 This Year : 38584

This Year : 38584 Total Users : 220389

Total Users : 220389 Views Today : 104

Views Today : 104 Total views : 1953086

Total views : 1953086 Who's Online : 1

Who's Online : 1