David B. Axelrod sent this text for Zwischenwelt way the hell back. It has recently been rejected by the same publication, and here are unpublished translations of poems by Axelrod in the original and in German translation. Axelrod proof read the English texts of Willy Verkauf-Verlon: Seiltänzer/Tightrope Walker. (Now available in Edition Tarantel, Vienna)

THE ART OF BEING TOO JEWISH

by David B. Axelrod

It was a very good summer for me in 1982. My career was taking off as a poet with a big New and Selected Poems just published and lots of performances. One prominent venue on Long Island, Guild Hall in fashionable East Hampton, scheduled me to perform and it was particularly gratifying as I would have so many friends and even some senior poets and mentors in the audience.

I had already lived on Long Island for a dozen years and the renowned poet, David Ignatow, had taken me under his wing. By then, he was in all the anthologies, as often for the poem about chasing a bagel! He’d won awards and grants, but to me he complained, “Never the Pulitzer.” Other senior poets presided in the Hamptons—like Michael Braude, Simon Perchik, Kenneth Koch, Phil Appleman, H. R.Hayes, Amrand Schwerner, Richard Elman, Stanley Moss, Frank O’Hara, Harvey Shapiro. Even John Hall Wheelock elderly as he was, was still actively writing.

Guild Hall was well-attended the night of my solo performance. I don’t call myself a performance poet, but I am known for my repartee between poems—even some jokes and “shtick” that liven up my presentations. I was particularly on the mark—or so I thought—that evening. Certainly, the audience laughed, and as is always the measure, the laughs were “on cue”—with me, not at me!

It ended with some gratifying applause but even before I could make my way off stage I saw a flange of three poets aiming at me at. It was Dave Ignatow, Michael Braude and Si Perchik rushing me from the back of the hall. They were visibly agitated. Reaching me, surrounding me, they said, all but in unison, “How could you do that?”#

“What did I do?” I asked, concerned I had crossed some unseen line of political correctness or propriety.

“You said all those Jewish things. You should never do that.” They were clearly horrified.

It had never occurred to me that would be an issue. The book had a little section of poems “For my Family” which even included a series of three poems for Jewish holidays. In the course of the reading I told a story about my Lithuanian Orthodox Jewish grandfather, Louis Axelrod, and even used a Yiddish accent. I read a poem about Hanukkah and my Russian grandfather Philip Kransberg and did a little shuckle that he used to do when he lit the menorah.

“It’s the kiss of death,” the threesome told me. Oh, how upset they were. How concerned I’d sunk myself. “Don’t you understand?” they berated me. You can’t ever get ahead if you are known as a Jewish poet.

Later, Dave Ignatow told me he really believed that folks like Untermeyer, a king maker in his days of his Golden Books Family Treasury of Poetry, and Robert Lowell with his “Brahmins,” were the ones. “I’d have had the Pulitzer if not for being Jewish,” Ignatow said. (Louis Simpson, got one, but he converted!)

Not long after, I picked up Howard Nemerov at the Port Jefferson, Long Island train station and hosted him for a reading at an event I sponsored. At a private dinner with me after, at which he drank more than his share, he was talking freely so I asked him, was it so? Was it so dangerous to be publicly Jewish as a poet. “Oh yes, absolutely,” he said. “Look at me,” he said. “What do they call me? An ‘epigramist’?”

Well, what can I do? I have a cousin who is very assertive about his Jewishness. I’ve told him about anti-Semites I met over the years; folks who wouldn’t rent an apartment to me if they knew I was a Jew, or even let me stay in their motel.

“I’d have taken them by the collar and punched them in the face,” my cousin hollered.

“I told them I was Welsh and got the place I needed to stay,” I confessed. But I’m no self-hating Jew. I may not be at all religious but I grew up glad for my cultural roots and there is one thing I also know. Try as a Jew may, pretend, put on airs, deny… One day just one little “Oy” will creep out and it will all be over!

That’s why I figure I might as well shout it out, even at a fancy East Hampton performance.

Video by Fritz Kleibel Vienna 2008

David B. Axelrod

Lyrik/Poems

Deutsche Übersetzung von Herbert & Irmgard Kuhner

Sophistry

The only god I’ve ever worshipped

is the bell-shaped curve.

1.

Life is a series

of random events.

Random events

produce a probability curve.

Probability patterns

guide our lives.

2.

What guides our

lives is god.

Probability guides

our lives.

The bell-shaped

curve is god.

3.

A lack of god means

life is random.

Random events

produce a pattern.

A lack of god

creates a god.

Sophistik

Der einzige Gott, den ich je verehrte,

ist die Glockenkurve.

1.

Das Leben ist eine Reihe

von zufälligen Ereignissen.

Zufällige Ereignisse

produzieren eine Wahrscheinlichkeitskurve.

Zufällige Muster

dienen als Leitfaden des Lebens.

2.

Was unser Leben steuert,

ist Gott.

Zufälligkeit lenkt

unser Leben.

Die glockenförmige

Kurve ist Gott.

3.

Ein Mangel an Gott bedeutet,

daß das Leben zufällig ist.

Zufällige Ereignisse

produzieren ein Muster.

Ein Mangel an Gott

schafft einen Gott.

In Munich

(from a New York Times report)

Gunther von Hagens’ „Körperwelten“ vastly successful anatomical exhibition of preserved bodies, first opened in Munich in 2003

* * *

Plasticized corpses are on display in a museum.

“I must be doing something right,” their creator says,

injecting the bodies of volunteers with a solution

that hardens into statues. “200,000 people

have viewed my work in just one week.”

Art critics say it’s art. Theologians argue

if it’s disrespectful. No one mentions

how the murder of 6,000,000 souls

also became an art.

In München

(aus einem New York Times Bericht)

Plastifizierte Leichen werden in einem Museum ausgestellt.

„Ich habe sicher das Richtige getan“, sagt ihr Schöpfer.

Er injizierte den Körpern von Freiwilligen eine Lösung,

die so hart wird, daß Statuen entstehen. „200.000 Besucher

haben meine Arbeit in knapp einer Woche besichtigt.“

Kunstkritiker sagen, sie sei Kunst. Theologen sagen,

sie sei respektlos. Niemand erwähnt,

wie der Mord an 6.000.000 Seelen

auch Kunst wurde.

The Man Who Said “Maybe”

He said a European flight

from Macedonia took more time

going than returning

because the earth turned favorably.

Try to explain the world a single entity – earth

sky and sea – he’d

listen patiently.

Next time he’d mention

travel, his theory

of anti‑gravity

was there again

more steadfast than

Galileo’s pendulum.

If a helicopter

hovered over a city,

would the next city

come along eventually?“

“Maybe.”

Der Mann, der „Maybe“ sagte

Er sagte

ein Flug von Mazedonien nach Westen

dauert länger als umgekehrt,

weil sich die Erde

nur in einer Richtung dreht.

Versuche ich,

ihm die Welt als Einheit zu erklären –

Erde Himmel und Meer –

würde er mir geduldig zuhören.

Wenn er das nächste Mal

vom Reisen sprach,

war seine Theorie wieder da –

unerschütterlicher als

Galileis Pendel.

Wenn ein Hubschrauber

über einer Stadt schwebte,

würde dann irgendwann

die nächste Stadt schließlich

unter ihm erscheinen?

„Maybe“

David B. Axelrod was born in 1943 in Beverly, Massachusetts. He is a Volusia County Poet Laureate, appointed to serve for a total of 8 years (2015 to 2023). He lives in Daytona Beach, where he is also founder and director of the Creative Happiness Institute, Inc. (CHI), a not-for-profit, educational organization that offers literary and cultural programs to the public.

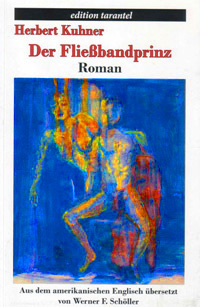

Edition Tarantel

Der Fließbandprinz

H. Kuhner

Willy Verkauf-Verlon: Seiltänzer /Tightrope Walker

Bilingual poetry

Tarantel Verlag, Wien

Willy Verkauf-Verlon artist and poet had a peripatetic life

which took him from Austria to Britain, Israel

and back to Austria again.

The poems reflect his Jewish odyssey with incision and humor.

They accurately depict post-war Austria and the world in general

as viewed by a Jewish individualist and non-conformist.

Willy Verlauf, Künstler und Lyriker, hatte ein paripathetisches Leben,

das ihn von Österreich nach Großbritannien, von dort nach Israel

und wieder zurück nach Österreich brachte. Die Gedichte spiegeln

seine jüdische Odyssee mit schneidender Schärfe und Humor wider.

Sie zeigen das Österreich vor dem „Anschluss“,

in der Kriegszeit und in den Nachkriegsjahren aus der Sicht

eines jüdischen Individualisten und Nonkonformisten.

Herbert Kuhner

Der Fließbandprinz

Roman Edition Tarantel 2017

Prolog

Zwei Musiker

Wir sind beide Konzertgeiger. Aber unsere Methode ist verschieden. Er ist der Ernste. Ich bin der Lässige. Er übt Tag und Nacht. Ich führe den Bogen über die Saiten, wenn ich dazu Lust habe. Kein Schweiß ist mein Wahlspruch. Ich schöpfe den Rahm von oben ab.

Er tritt immer in einem paradiesisch geschneiderten Frack auf. Manchmal trage ich einen Frack, manchmal tut es auch ein Smoking. Ich benütze immer eine Variation, wie etwa einen Rollpulli oder eine Schuhbandschleife. Ich trete sogar in einem T-Shirt bei Konzerten auf. Das Publikum liebt das. Von ihm kann ich nicht das Gleiche sagen. Nicht, daß er kein Künstler wäre. Niemand kann auf die Art und Weise spielen wie er. Ich weiß, daß ich nicht halb so meisterlich bin wie er. Ich sage das nicht aus Bescheidenheit. Bescheidenheit ist nicht eine meiner Charaktereigenschaften. Aber eine Tatsache ist eine Tatsache. Ich brauche nicht stolz auf mein Spielen zu sein. Warum sollte ich? Es ist nicht notwendig.

Er tritt immer in einem paradiesisch geschneiderten Frack auf. Manchmal trage ich einen Frack, manchmal tut es auch ein Smoking. Ich benütze immer eine Variation, wie etwa einen Rollpulli oder eine Schuhbandschleife. Ich trete sogar in einem T-Shirt bei Konzerten auf. Das Publikum liebt das. Von ihm kann ich nicht das Gleiche sagen. Nicht, daß er kein Künstler wäre. Niemand kann auf die Art und Weise spielen wie er. Ich weiß, daß ich nicht halb so meisterlich bin wie er. Ich sage das nicht aus Bescheidenheit. Bescheidenheit ist nicht eine meiner Charaktereigenschaften. Aber eine Tatsache ist eine Tatsache. Ich brauche nicht stolz auf mein Spielen zu sein. Warum sollte ich? Es ist nicht notwendig.

Er spielt herrliche Konzerte. Aber sie enden immer in derselben Art und Weise: mit einem Knall und einem Durchfall. Das Publikum läßt ihn selten zu Ende spielen. Er wird gewöhnlich im Mittelteil unterbrochen. Er wird ausgepfiffen, niedergebrüllt und ausgelacht. Und man wirft Obst und Gemüse nach ihm. Die Belohnung für sein schönes Spiel ist ein Fußtritt. Und wenn ihm zufällig die Beendigung des Konzertes gewährt wird, jagt man ihn aus der Stadt, sobald es aus ist.

Und da er altert, wird es immer schwieriger für ihn, Engagements zu bekommen. Aber trotz allem liebt er sein Publikum und erklärt ihm seine Liebe. Ich verachte mein Publikum. Wenn ich auf der Bühne zu erscheinen geruhe und mir die Mühe mache, mein Instrument anzusetzen, hält es den Atem an vor Erwartung. Arme Narren! Ein bloßer Zupfer an den Saiten, und ich habe sie in meiner Hand. Ein Pizzicato genügt, um sie in Ekstase zu versetzen. Ich ziehe den Bogen über die Saiten, und sie werden in den Wahnsinn getrieben.

Users Today : 152

Users Today : 152 Users Yesterday : 165

Users Yesterday : 165 This Month : 2134

This Month : 2134 This Year : 19067

This Year : 19067 Total Users : 177162

Total Users : 177162 Views Today : 366

Views Today : 366 Total views : 1867601

Total views : 1867601 Who's Online : 11

Who's Online : 11